Scripting Change: How ‘Taht El Wesaya’ could Reshape the Guardianship Law in Egypt

Taht El Wesaya(Under Guardianship) continues the tradition of Egyptian TV dramas created to fight patriarchy through scripted performances as it discusses the guardianship role in the Code of Personal Status in Egypt.

As an ardent fan of women-oriented TV dramas that follow women’s journeys into the patriarchal societies we live in, I could not resist but write down a few thoughts about one of the most intriguing TV dramas this year.

You May Need Your Handkerchief, It’s a Sad Story!

Under Guardianship takes viewers on the captivating journey of Hanen, starred by the exceptional Mona Zaki; a widow with two kids, Yassine and Farah, who struggles to find her way back to her decent life after her husband’s death. The plot discusses the implications of the Guardianship Law in Egypt that privileges the parental grandfather or a guardian nominated by the father with the right to guardian the late father's children, denying the mother any right to be the guardian herself. Under the umbrella of legal conflicts over the destiny of Yassine and Farah, the plot, with each episode, unfolds a different struggle such as the preconceived notion of a woman’s inability to succeed in a male-designated job like sailing, sexual harassment, and exploiting the protagonist’s physical and emotional vulnerability.

The first encounter with Hanen provides insufficient information about her identity except for being a woman on the run with two kids. Yet, as events progress, they gradually reveal snippets of Her backstory through the flashback technique. Her ordinary look can be fathomed as she might be kept within the frame of conventionality. The most noticeable physiological characteristic is her thick eyebrows providing cues into her the struggles she faced due to her social status as a widow, while mutually paving the way for other events and frustrations that would leave no space for self-care. Additionally, the burdens that come with being the only woman in the middle of the sea with other men can be navigated through her attire. The way she was dressed was meant to showcase her petite morphology vis-à-vis three sailors with a typical stereotypical look towards women and thus, provide insights into a physical vulnerability that was later transformed into more moral battles.

An Expected Ending that Hides Unexpected Complexity

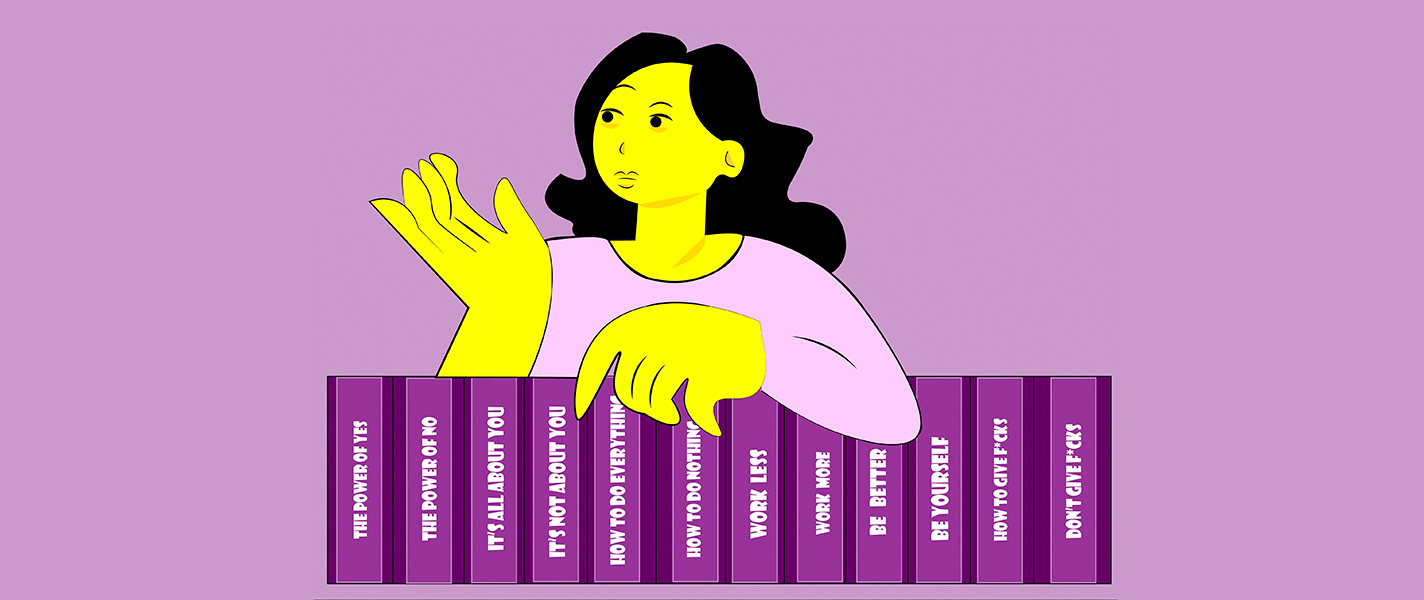

Along with the storyline’s ability to introduce provoking ideas simultaneously, what genuinely distinguishes the plot is its realistic ending that exceeds the boundaries of the ‘happily ever after’ resolution. Sentencing the heroine to imprisonment may speak out the authors’ intention in prompting the viewers to reflect upon the situation of hundreds of women like Hanen in Egypt. It emphasizes that satisfying those behind the screen with an eventually happy heroine is temporary and purely fictional, which contradicts with a heartbreaking and realistic ending that could drive further discussion and the possibility for genuine change.

From a subjective perspective, the lack of dramatic intensity in the trial scene in the finale is what, ironically, contributed to creating its emotional depth. Hanen’s not-very poetic speech when she was talking about her children’s needs- unaccompanied with an emotional musical effect-, and most importantly, the judge’s answer: “What you’re saying does not exist in the Law. And I only speak in the language of the Law”, stress the previously emphasized female frustration with the Guardianship Law. It also provokes further questions about the role of mothers and the overall conception of motherhood as rhetorically asked by the main character on several occasions throughout the series. Yet, the simplicity of her speech defies an entire philosophy that no longer women can handle.

Despite being sentenced to a year in prison, the main character has succeeded in proving that sailing can be a gender-neutral profession, marking another victorious moment for women's leadership in a patriarchal society. Gaining the support and respect of the sailors working with her by the end of the series, and potentially finding love again can be considered as a dramatic compensation for the inevitably cruel reality served to the viewers.

Change This Time Is Not Fictional!

Since its premiere on Television, the series has become a symbol of triumph among the Arab series during the holy month of Ramadan as it has generated continuous discussion about the possibility of the amendment of the Guardianship Law in Egypt. The positive response of the Egyptian president to amending this law sets the series as a change-agent show in the long term that goes beyond a transient identification with a struggling character. That is, it answers the question ‘Why not the mother?’ by inspiring lawyers to submit requests that reconsider widows’ rights to be the legitimate guardians to their children.

The responsive reactions of some legal representatives in the country have revoked the reciprocal relationship between artistic productions and the political climate. Creating Female characters such as Hanen in this series and Faten in Faten Amal Harby who strives to change the Law that threatens women’s custody of their children if they remarry unveils the strategy of shifting the Egyptian drama towards non-sexualized female-centered plots.

With its cultural relevance and immersive plotline, Under Guardianship dared to spark further conversations about the necessity for change. The progress achieved thus far in relation to reconsidering the law proves that Hanen's experience depresses the boundaries of fiction to represent hundreds of women from all social paths.

The article represents the views of its writer and not that of LEED Initiative.