L’école laïque” and the Colonial Leftovers

There is a moment in everyone’s personal history that reconjures itself as an inflammatory thought. Registering it as a mere memory or as a foreign self outlines the depth of your trauma. And oftentimes you find yourself with a crater at the back of your mind. That is where the dark matter, the abscess, and the crises form. For me it is this thought: It starts with a memory of being seated longer than necessary and with words that mean nothing to my current state of affairs, yet they stranglehold the world as they are being spoken. If you haven’t got a lecture from a middle-aged person about the history of colonization, you’ve experienced, without knowing, a great loss, one that I still fail to put into significant words...

A Slow-Burning Imprint:

It always ends with a surge of hot blood that turns cold as it gets to your senses. The ones about French conquests always have a je ne sais quoi to them, quite literally. You will only realize how long the person has spoken by the white formations on both sides of their mouth. The closer they get to independence the readier you are to be launched, a meld of postcolonial and nationalistic aspirations by transmission, a hero without a cause. But if at that moment you were lucky, less passionate, and perhaps heedful rather than lost in your thoughts, you’ll see the elephant getting bigger, until it becomes the room. For me, it was one word repeated three times, “Secularism! Secularism! Secularism!”, and was immediately followed by a glint in the eyes of the speaker that I later realized was the reflection of my stars falling from high above.

Secularism vs. Laïcité:

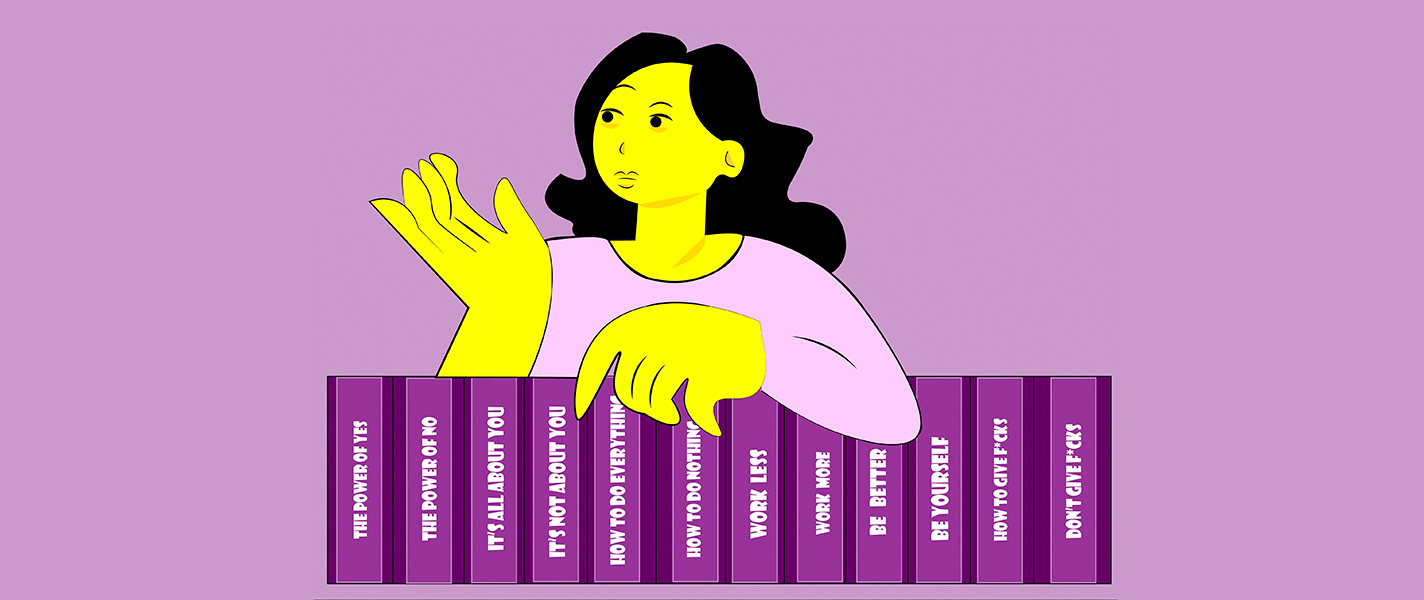

Whenever someone from my community invokes secularism, it's essential to recognize that this term is a mistranslation of "laïcité." But where lies the distinction? Is it a matter of totality versus partiality, or perhaps radicalism versus moderation? These distinctions are, in general, pertinent, but are of little relevance to this issue. The crux of the matter is that the former is a preference, a necessity at best, while the latter carries the weight of those who purportedly were never subject to colonization.

Origins of "L’école laïque":

“L’école laïque” was first legally recognized with the passage of the laws of 1881-1882, establishing free, secular, and compulsory public education in France. It is almost hard to distinguish them from the work of Jules Ferry, the head of the government and the Minister of Public Instruction at the time. Jules Ferry had a dual identity: that of an enlightened democrat and promoter of progressive reforms within the country, and that of a theorist and zealous architect of colonial expansion, which he pursued, in part, by leading France into the Tonkin War and, more notably, to the conquest of Tunisia ‘the protectorate’, in April-May 1881.

Externalizing the Secular Agenda:

Outsourcing the secular project that began in the French peripheries: Brittany, the Basque Country, or Occitania, to the people of Tunisia, was not different from missionary work (as a colonial apparatus) and was closer in practice to religious proselytism than to any liberal or nationalistic ethic. The prospects of modernization were gradually being accepted by an ever-illusioned majority. But did these secular reforms have the same liberating consequence on the sons and daughters of Breton farmers as on those of Tunisian farmers? Hardly.

The Inapplicability of Secularism:

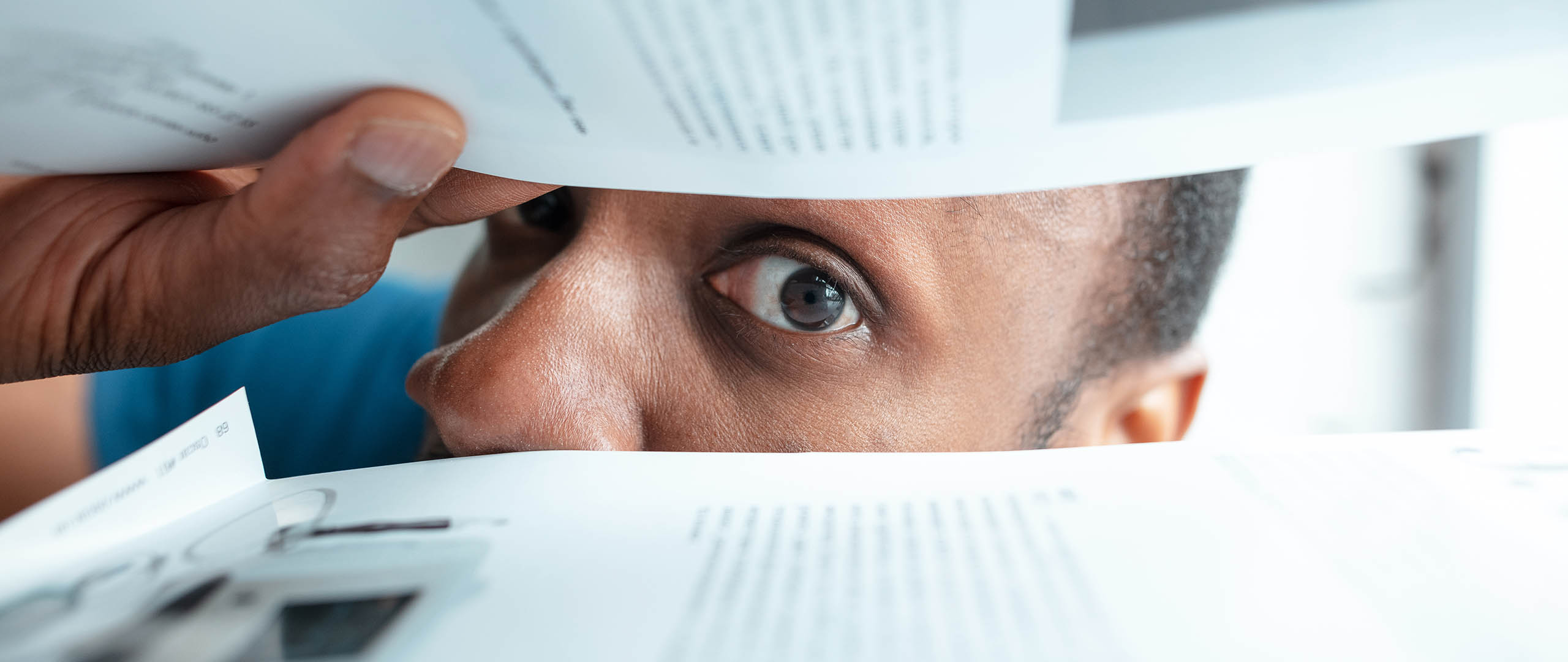

In 1883, during the establishment of the Directorate of Education, Tunisia had 24 schools teaching in the French language, out of which 20 were led by members of religious congregations, and only 4 were led by secular teachers. Twenty years later the number of schools run by secular teachers reached 135 (with almost 16,000 students). In 1893, in Sousse, for instance, the secular boys' school enrolled 7 French students and 182 Muslim students, while the girls' school enrolled 13 French, 10 Italian, 4 Maltese, and 156 Jewish students. On the other hand, the congregational boys' school had 51 French, 21 Italian, 75 Maltese, and 27 Jewish students. The congregational girls' school enrolled 57 French, 46 Italian, 68 Maltese, 1 Muslim, and 36 Jewish students. Thus, Muslims and Jews seemed to have a firmer inclination toward secular schools, in certain locations more than others. These schools were associated with Muslims and/or Jews, whereas Italians, Maltese, and even Catholic French students tended to favor congregational schools. Potential problems lay between Catholicism and secularism, as in ‘the metropolis’, rather than between Islam or Judaism and secularism.

This is to say that the nature of the Tunisian people and their religious variance never required the secular alternative that France proceeded to offer as a solution. One might argue that, outside any political agitation, even without the ‘mediation’ of France, Tunisia would have produced the same specimen of homogeneity. Much like the secular reforms that France enforced, the problems with these solutions were also exported and entirely outsourced. But for what end?

Economic Gain and Colonial Ambitions:

The reality is that Tunisia was not initially seen as a land of vast riches or a lucrative market for capital export. Economic arguments against the colonial policy were more common than those in its favor. However, some recognized potential gains, chiefly among them was Ferry: "At this time, as you know, a warship cannot carry more than fourteen days' worth of coal, no matter how perfectly it is organized, and a ship which is out of coal is a derelict on the surface of the sea, abandoned to the first person who comes along. Thence the necessity of having on the oceans provision stations, shelters, and ports for defense and revictualling [an interesting term now used synonymously with ‘trade partner’]. And it is for this that we needed Tunisia..." He explained.

The role of “L’école laïque” in the projects of acculturation and ‘civilization’ justified by reform ambitions and national unity hardly masked Ferry's strategy for cost-effective expansionism. Over time, this system became self-sustaining as Tunisian proto-nationalists emerged to further the advocacy for ‘European-inspired’ modernization and increase Tunisian ‘engagement’ in governance. Yet they were naturally too close to the French to ask for more.

Legacy of Colonialism and “L’école laïque”:

It is not so difficult nowadays to discern the remains of this imperialist project in the current political and intellectual landscapes of Tunisia. What we should recognize in the feudal atmosphere that sustains the ongoing autogolpe is an irresolvable complex of inferiority, a suffocating intellectual indebtedness, and a dependence on the colonial patriarch for validation, which our postcolonial rhetoric fails to shroud.

We could surely fashion a more nurturing alternative to celebrate our differences, our unity, and our free being than what the cold leftovers of colonialism would provide. All this is to say that secularism and laïcité are two different words, two different histories, and one should be careful about which history to call for, or even call back.

The article represents the views of the blogger and not those of LEED Initiative.