The Cost of Participating in Politics as a Young Person

Over the past three years, I’ve worked with dozens of young people in multiple political parties and activists. In progressive spaces, these people are generally well-meaning, intelligent, and introspective regarding their involvement in politics and what it signifies. But problems persist in the micro-culture of “youth in politics,” and they stem from the exclusivity of the space itself.

Active participation in politics has always been a privilege reserved for a few, from the times of racist, sexist, and colonial systems of exclusion, through to the present day. Even in democratic systems where everyone has the right to vote, the financial and time costs of participating in election campaigns, political parties, or non-partisan civil society groups remain high. Unions, which are an important way for workers to become politically engaged, are consistently opposed by big business. The democratization of workplaces and political institutions alike remains a key battlefront in the fight for social progress.

Beyond voting, present-day participation in democracy is mainly limited by time — the time to vote and to participate in other aspects of the democratic process including partisan processes. Membership fees can also be a barrier in this regard. Employment opportunities in the civil service or non-profit sector, critical for the functioning of a democratic society, are always limited and often reserved for those with prior experience.

“Youth in politics” and their incentives

For young people, the barriers to entry have consistently been higher than for their elders: Less experience, less disposable income, and often less free time, too. Among those who manage to find a comfortable place for themselves in political spaces, the selection bias is such that there’s a good chance they are the beneficiaries of privileges their peers lack. This applies to participants in the aforementioned election campaigns, political parties, and even civil society groups.

This explains why the youth wings of political parties, or other youth-led groups, rarely grow beyond the small cadre of dedicated members who occupy leadership positions into a genuine mass movement (or even a slightly bigger cadre). The young people who end up in positions of leadership within these organizations need to be more incentivized to dilute the benefits they receive from being part of a political apparatus by increasing the participation of other youth. These benefits are not insignificant: Access and proximity to power (or even just the perception of power), and employment opportunities are just some of the benefits of being a “youth in politics.”

There are also benefits to being perceived as the founder of a group. Redundancies in activism and politics emerge some when young people are compelled to start new initiatives by the prestige of leadership roles, rather than accept a smaller role in helping an existing initiative. This results in a fragmentation that serves CVs at the expense of effective organizing.

This also explains why young people can sometimes act as accomplices to their tokenization. The roles and honors set aside for young people, on youth advisory boards and youth councils, help build CVs. What emerges is a reciprocal relationship between adults in positions of power and young people who aspire to those same positions in which the former offer resume-building opportunities and the latter legitimize the organization’s commitment to including youth. To be clear, these are not genuine partnerships in which the youth involved get a say in how the organizations are run, or the direction of future organizing.

A path forward

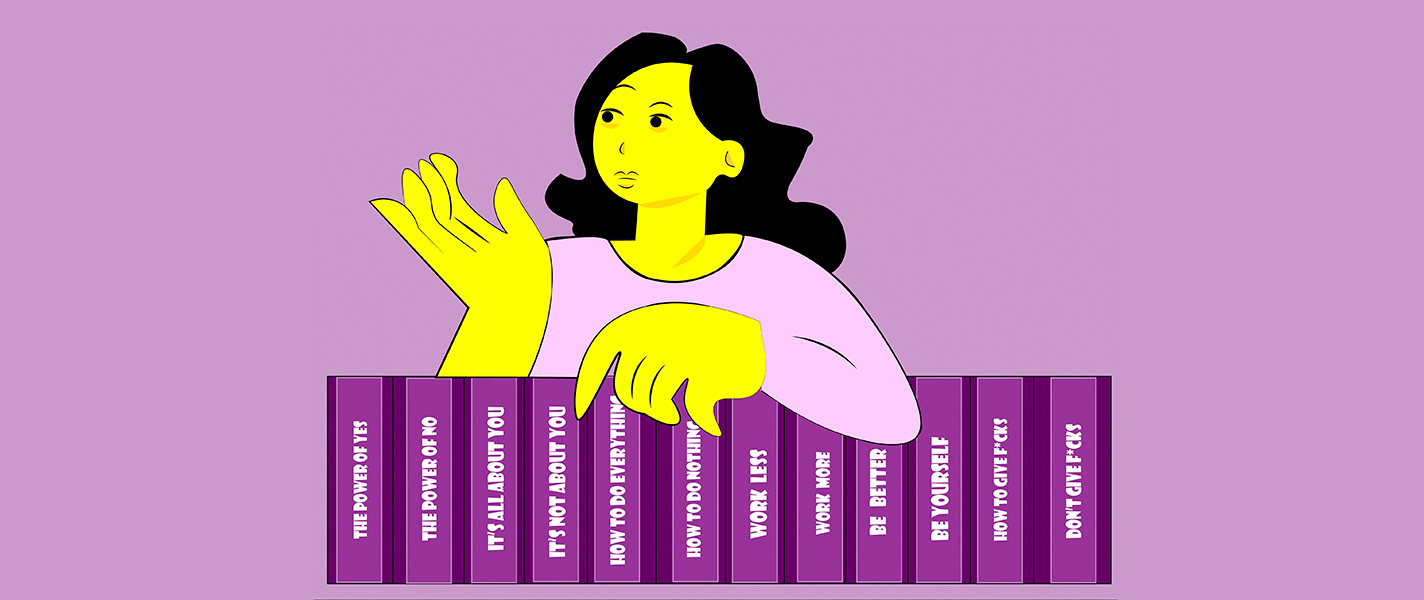

None of this is to blame young people — particularly minors — for being misled by organizations that on the surface work towards noble causes. But young people operate in much larger systems, and they are not immune to those systems’ incentives, nor the mistakes of prior generations. Those young people who do have the privilege to participate in politics often want to keep that privilege exclusive.

Young people are so underrepresented in politics that those who do participate come to believe that their participation is a good thing in and of itself. But political involvement comes with its own set of responsibilities, not least of which is broadening the range of people who can participate. There are certainly more extreme examples in right-wing spaces: In my home country of Canada, some young people have leadership roles in the youth wings of parties that support targeting trans kids in the name of “parental rights” for political gain. Needless to say, I don’t think their participation is a net benefit for young people.

I remain committed to being a “youth in politics” for as long as I can still be considered young. But trying to make progressive change comes with a responsibility to include others in the process of change-making. My own experience in leadership positions has been guided by the goal of working myself out of a job — of creating opportunities for others and not just myself. I’m not exceptional and have seen many others do the same. But as a general rule, it’s never too early for young people entering politics to ask themselves: “What am I leaving behind for others?”

The article represents the views of the blogger and not those of LEED Initiative.